AUCTORES

Globalize your Research

Research Article | DOI: https://doi.org/10.31579/2578-8965/095

1Associate professor Maternal and Newborn Health Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Beni-Suef University, Egypt

2Professor of Maternity & Neonatal Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Cairo University, Egypt

3Professor of Obstetrics and Women Health Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Benha University, Egypt

4Assistant lecturer of Maternal and Newborn Health Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Beni-Suef University, Egypt

*Corresponding Author: Hanan Elzeblawy Hassan, Associate professor Maternal and Newborn Health Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Beni-Suef University, Egypt.

Citation: Hanan E Hassan., (2021) Impact of an Educational Program on Sexual Issues among Cervical Cancer Survivors' Women in Northern Upper Egypt. J. Obstetrics Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences 5(1); DOI: 10.31579/2578-8965/095

Copyright: © 2021, Hanan Elzeblawy Hassan, This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received: 15 February 2021 | Accepted: 27 February 2021 | Published: 12 March 2021

Keywords: cervical cancer; sexual dysfunction; sexual distress

Background: Sexuality is an important part of normal human functioning. Gynecological cancer and its treatments can affect one or more phases of the sexual response cycle, through alterations of sexual function. Sexual dysfunction is one of the most distressful symptoms among cervical cancer survivors. Sexual distress is a broad term encompassing any sexual discomfort and dysfunction. Sexual difficulties following cervical cancer can be stressful for couples as it can feel like a core part of the relationship has disappeared.

Aim: The study is conducted to evaluate the impact of an educational program on sexual issues (sexual dysfunction & sexual distress) among cervical cancer survivors' women in Northern Upper Egypt.

Methods; Design: A quasi-experimental design. Setting: out-patient clinic in the oncology unit at Beni-Suef University Hospital. Subjects: A purposive sample of 70 women. Tools: structured interviewing questionnaire sheet, female sexual function index, and female sexual distress scale.

Results: The results of the study revealed regression of all items of women’s sexual distress scores, and progression of all items of women’s sexual items post-program compared to pre-one.

Conclusion: The teaching program was very effective in improving sexuality among cervical cancer survivors' women.

Recommendations: Disseminate the educational booklet at health centers and oncology outpatients. Integrate psychologist, psychosexual specialist, and social worker in treatment and counseling program for women with cervical cancer in the early stage of their treatment.

Cervical cancer affects all aspects of a patient’s life, including sexual functioning and intimacy. [1-3] Health care providers don’t ask patients about it, and women may be uncomfortable broaching the topic on their own. Sexual dysfunction poses challenges to one’s social, mental, emotional and physical wellbeing. [4] It may occur as a result of the nature of a cancer, such as a cancer that affects the mechanics or hormonal pathways in sexual function, as a result of the treatment such as surgery, chemotherapy or radiotherapy. It may also occur from the emotional trauma of receiving a diagnosis. [5]

Gynecological cancer and its treatments can affect one or more phases of the sexual response cycle, through alterations of sexual function. The high curability of cervical cancer, when detected early, combined with the latest scientific advances in medical treatment, has contributed to greater survival of patients. However, treatment of this neoplasm can, on the other hand, lead to late adverse effects, primarily related to radiotherapy, caused by its action on healthy tissue and organs adjacent to the tumor. The areas most affected are the vagina, bowel, and bladder, which undergo changes in the mucosa. [6-8]

Sexual distress is a broad term encompassing any sexual discomfort and dysfunction that includes decreased libido, difficulty achieving orgasm, dyspareunia, vaginal dryness, and vaginismus. [9-11] In fact, sexual distress can cause stress and anxiety in individuals. Researchers have found that sexual distress is present in all stages of cervical cancer treatment and during follow up. [9]Pitche et al, (2018) define sexual self-concept as a psychological and cognitive constructs relating to how one experience and understands one’s sexual identity. [12] A fulfilling sex life is important to many couples as it is an opportunity for bonding, intimacy and quality time. Sexual difficulties following cervical cancer can be stressful for couples as it can feel like a core part of the relationship has disappeared. [10]

In gynecological cancer Ratner et al., (2014) reported that between 30% of the women that underwent treatment for cervical cancer experienced some sexual problems and most of the women are at greater risk for developing vaginal stenosis and agglutination within the first three months of radiotherapy. [13]

Causes of sexual dysfunction following cervical cancer treatments may be multi-factorial but it may often result from the direct effects of the treatment. With an aging global population, improved diagnosis and better cancer treatments, more people surviving cancer. Despite recognition of the problem, sexual morbidity remains under-treated in these patient groups. This is, in part, because of the embarrassment associated with sexual dysfunction not only from the patient’s point-of-view but from that of clinicians. [14] Sexual dysfunction is one of the most distressful symptoms among cervical cancer survivors. Cancer treatment including radiotherapy results in a high degree of vaginal morbidity and persistent sexual dysfunction. Vaginal symptoms reported after cervical cancer treatment; sore membranes, reduced lubrication and genital swelling severely affect the women’s sexual health. [15-21]

Nurse is a caregiver for patients and helps to manage physical needs, prevent illness, and treat health conditions. [22-24]. To do this; nurses need to observe and monitor the patient, recording any relevant information to aid in treatment decision-making. Throughout the treatment process, the nurse follows the progress of the patient and acts accordingly with the patient’s best interests in mind. [25-27]. The care provided by a nurse extends beyond the administration of medications and other therapies; nurses are responsible for the holistic care of patients. [28, 29] Communication is a vital element in nursing in all areas of activity as prevention, treatment, therapy, rehabilitation, education and health promotion. The nursing process moreover as a scientific method of exercise and implementation of nursing, is achieved through dialogue, through interpersonal environment and with specific skills of verbal communication. Therapeutic practice involves the oral communication of public health officials and nurses on the one hand and the patient or his relatives on the other. [30]

Maternity and oncology nurses among health care providers are in the first degree to which women can easily explain themselves and can be effective in removing their concerns related to sexual health. [31] Oncology nurses are expected to fulfill a variety of activities such as information giving, symptom control, psychological care and social support for the patient. [3] Maternity nurses have important duties as a counselor and guide in determining the factors affecting sexual functions of cancer patients, problems that may be experienced in sexual matters, and providing help to these individuals in order to get over these problems. [32]

The loss of fertility and sexual changes related to surgical treatment of cervical cancer can be very traumatic for some women. Nurses working with patients that are dealing with this type of issues have to be able to comfortably discuss sexual issues and provide a non-threatening environment for patients where they can ask questions on this own. Furthermore, women with cervical cancer need a lot of support and may require interventions from social work and psychological counseling in the early stage of their treatment. It is up to the nurses to create a collaborative plan of care for these patients and coordinate its components. [33]

Molina & Gallo (2020) argue that in order to meet patient’s needs, care provided by nurses should be holistic and individualized. This may include individualized pain interventions, or for instance tailored follow-ups. In their study, noticed that patients receiving telephone follow-ups expressed high levels of satisfaction with their care and preferred telephone contact over usual physician appointment due to greater convenience. [34]

The nurse also guides the cervical cancer survivor to regain self-confidence and adapt to physical and psychological changes to optimize survivor autonomy. [1, 6] Nurses provide psychosexual counseling can significantly improve sexual function in patients with gynecological cancer. Education and counseling for women after cancer treatment may also reduce sexual problems and improve intimate relationship. [35]

Survivors of cervical cancers and their spouses need help from health care personnel, especially nurses, to overcome their sexual problems. Providing psychosexual health care is one of the important roles for nurses that work at a cancer unit. [36] Other studies have provided scientific evidences that intervention on counseling education may improve complaints of sexual dysfunction, reducing anxiety and depression, which finally may lead to increased quality of life in women following treatment of cervical cancer. [37]

While some people find sexual intimacy is the last thing on their minds after treatment, others experience an increased need for closeness. An intimate connection with a partner can make patient feel loved and supported as come to terms with the impact of cancer. However, cancer can complicate relationship, particularly if the patient had relationship or intimacy problems before cancer diagnosis. [38]

Sexuality and intimacy after cancer may be different, but different does not mean better or worse. The favorite sexual positions may become less comfortable temporarily or changes over time. To adapt to these changes, women may need to develop more openness and confidence, in and out of the bedroom. Try to keep an open mind about ways to feel sexual pleasure. [39]

Changes after cervical cancer treatment may include vaginal shortening or narrowing, and decreased vaginal lubrication. In addition, women that were premenopausal before treatment may become postmenopausal as a result of pelvic radiation, surgical removal of the ovaries, or chemotherapy. These physical changes impact sexual satisfaction as it may lead to pain during intercourse, difficulty having intercourse because of narrowing or shortening of the vagina, lack of interest in sex, and difficulty having an orgasm [40].

The most common problems related to sexual dysfunction in women with cervical cancer is inhibited sexual desire. This involves a lack of sexual desire or interest in sex. Many factors can contribute to a lack of desire, including hormonal changes, medical conditions, treatments, depression, stress, and fatigue. Regular sexual routines and lifestyle factors, such as careers and the care of children may contribute to a lack of enthusiasm for sex. [41] For women, the inability to become physically aroused during sexual activity after cervical cancer treatment often involves insufficient vaginal lubrication. This inability also may be related to anxiety or inadequate stimulation. In addition, researchers are investigating how blood flow problems affecting the vagina also clitoris may contribute to arousal problems. [42] Painful intercourse (dyspareunia) can be caused by poor lubrication, the presence of scar tissue from surgery, a sexually transmitted disease and decreased lubrication following cervical cancer treatment. Vaginismus is a painful, involuntary spasm of the muscles that surround the vaginal entrance. It may occur in women that fear & think that the penetration will be painful. [11,43] Nurses play a vital role in health care provision; nurses provide the majority of direct patient care. In addition to performing routine medical procedures, also play many other important roles (educator, care giver, counselor, manager, and researcher). Nurses educate patients regarding medications, diseases, treatment, life style changes, and discharge from hospital. This education can be informal, part of daily care or given in more formal teaching [44]

Norouzinia et al., (2016) added that a good approach for conveying information requires good communication skills, trust, ability to listen and competence on the part of the nurse or health care professional. Education and counseling on sexuality are nursing interventions used to assist patients to resolve their sexual problems. In nurse-led counseling oncology nurse provides information and assists patients in making and executing a decision. [45]

Sexual oncology is gaining appreciation as major area needing attention in nursing practice and research. Oncology nurses need to possess a high level of sensibility in dealing with patients’ sexual health. However, sexual health care still inadequate addressed due to barriers such as incorrect assumptions and beliefs toward sexual issues. Nurses are at the first degree, among health providers in which cervical cancer patients can easily contact and can be effective in removing their problems related to their sexual health. [46-51]

1. Aim of the study

The study is conducted to evaluate the impact of an educational program on sexual issues (sexual dysfunction & sexual distress) among cervical cancer survivors' women in Northern Upper Egypt

2. Hypothesis

Women with cervical cancer that attended the conducted program will experience progression in sexual function and regression in sexual distress.

3. Subjects and methods

1. Research Design

A quasi-experimental (pre-post) test study design was used.

2. Setting

The out-patient clinic in the oncology unit at Beni-Suef university hospital.

3. Subjects:

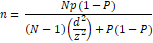

n= Np(1-P)N-1d2z2+P(1-P)

N= Population (140), Z= confidence level 95% (1.96), P= probability (10%), d= margin of error (0.05)

4. Tools of Data Collection

To attain the aim of this study, three tools were used for data collection;

1. Tool I: Structured interviewing questionnaire sheet. It was consisting of Socio-demographic characteristics, and medical & surgical history, and obstetrical history of women, as well.

2. Tool II: Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI). A multidimensional self-report questionnaire that assesses the key dimensions of female sexual function during the four weeks prior to the interview day.

The individual domain scores and full scale (overall) score of the FSFI can be derived from the computational formula outlined in the table below. For individual domain scores, add the scores of the individual items that comprise the domain and multiply the sum by the domain factor (see below, table 1). Add the six domain scores to obtain the full scale score. It should be noted that within the individual domains, a domain score of zero indicates that the subject reported having no sexual activity during the past month. Subject scores can be entered in the right hand column. A total score of 28.1 was taken as the cutoff point for the Arabic version FSFI to distinguish between women with FSD and those with normal function.

3. Tool III: Female sexual distress scale; it revised for assessing distress in women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. This is a self-report questionnaire designed by Derogatis et al., (2008). [53]

Scoring system for tool III (Female sexual distress scale):

This tool consists of 13 items to assess different aspects of sexual activity-related distress in women. Women were asked to choose the number that defines the frequency of discomfort of the sexual problem she has had in the last 30 days. All items are scored on a five-point Likert scale. Responses ranged from zero (never) to 4 (always), the total scores to be received are between 0 and 52 with a higher score indicating more sexual distress; women receiving 11 or higher points was deemed to have sexual disorders.

2. Validity and Reliability:

Before starting the fieldwork, the developed tools were reviewed by 3 specialists in the maternity specialty and their comments were considered. Cronbâch alpha and Spearman-Brown coefficients were calculated to assess the reliability of the developed tools through their internal consistency.

3. Administrative & Ethical Considerations:

Before conducting the study, official permission was obtained from the director of Beni-Suef University Hospitals. Consent was obtained from each woman recruited in the study. Participants' were told that all their data were highly confidential. Informed oral consent was obtained from women after explaining the purposes of the study.

4. Field work:

3.7.1. Preparatory phase:

It was included reviewing of local and international related literature and theoretical knowledge about various aspects of the study problem. Then the researchers tested the validity of the tool through jury of expertise to test the content, knowledge, accuracy & relevance of questions for tools.

3.7.2. Pilot study:

A pilot study was conducted on 7women to evaluate the applicability, efficiency, clarity of tools, assessment of feasibility of field work and identification of suitable place for interviewing women.

3.7.3. Data collection phase

The data was collected through a period of six months from the 1st of August 2019 till the end of January 2020. The researcher introduced herself to women and explains the aim of the study prior to data collection. Filling questionnaire ranged from 15-20 minutes from a woman. The sexual nursing counseling was given by the researcher at the outpatient unit in three meeting sessions. Weekly follow up by using telephone call for instruction & reinforcement about items of sexual counseling. The effect of sexual nursing intervention was evaluated through comparing between the women's condition (sexual dysfunction, and sexual distress) pre and post-intervention after1 month.

5. Statistical analysis

The collected data was revised, coded, tabulated and introduced to a PC using statistical package for social sciences (IBM SPSS 25.0). Statistical significance was considered at p-value <0.05. Data was presented and suitable analysis was done according to the type of data obtained for each parameter

Results

Figure (1) reveals that approximately slightly less than one-quarter (21.4%) of the study sample their age ranged from 30 to < 40 years old and more than half (51.4%) their age more than 50 years old. Regarding educational level of women slightly less than half (48.6%) had secondary education. Regarding occupation more than half (64.3%) of women were housewives. Regarding residence more than half (52.8%) of women was from urban areas and more than half of them (57.1%) Their age at marriage was less than 20 years old.

Figure (2) shows that slightly less than three-quarters (72.8%) the studied women had diagnosis of cervical cancer from signs and symptoms more than one-third (35.7%) of women were in the 1st degree when diagnosed with cervical cancer while (4.3%) were in the 4th degree. Regarding treatment type more than one-third (37.1%) of women had received radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and surgical operation, more than three-quarters (81.4%) of women had total hysterectomy. Regarding medication side effects; more than one third (40%) of the studied sample had diarrhea, hair loss, tiredness, and anemia.

Figure (3) illustrates that more than three-quarters (78.6%) of the studied women had menarche by the age of 12-15 years old while only 2.8% of women had menarche after the age of 15 years old. Regarding menstrual regularity, slightly less than half (41.4%) of studied women had amenorrhea and one-quarter (25.7%) had regular menstruation. Regarding number of parity more than half (62.8%) of women had more than three deliveries and only (1.4%) were nulliparous.

Figure (4): Portrays percentage distribution of women’s total sexual dysfunction & sexual distress, it illustrates that all women (100.0%) of the studied women had sexual dysfunction at pre-program while changed to (50%) at post-program. Moreover, the same figure reveals that more than three-quarters (88.6%) of the studied women had sexual distress at pre-program and all (100%) of them were free from sexual distress at post-program

Figure (5): portrays women’s sexual functions indicators regarding sexual desire & sexual satisfaction pre/post-program implementation. It reveals an improvement in women's sexual desire (FSFI 1&2) and sexual satisfaction (FSFI 14, 15, 16) after attendance of the conducted program.

Figure (6): portrays women’s sexual functions indicators regarding sexual arousal pre/post-program. It illustrates improvement in women's sexual arousal (FSFI 3,4,5,6) after attendance of the conducted program.

Figure (7): portrays women’s sexual functions indicators regarding vaginal lubrication pre/post-program. It reveals improvement in women's vaginal lubrication (FSFI 7,8,9,10) after attendance of the conducted program.

Figure (8): portrays women’s sexual functions indicators regarding sexual orgasm pre/post-program. It highlights the improvement in women's sexual orgasm (FSFI 11,12,13) after attendance of the conducted program.

Figure (9): portrays women’s sexual functions indicators regarding pain (dyspareunia) pre/post-program. It reveals improvement in women's pain (dyspareunia) (FSFI 17,18,19) after attendance of the conducted program.

Figure (10) summarized the improvement in all items of the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI); (19-Multiple-choice-questions that measure 6, domains, including desire domain, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and sexual pain) after application of the educational program compared to pre-pregame.

Figure (11) reveals regression of all items of women’s sexual distress scores post-program compared to pre-one. In pre-program; more than half (64.3%) and more than one-third (41.4%) of the studied women had felt frustrated and stressed about their sexual problems respectively, also more than one-third (38.6%) of them had felt embarrassed about their sexual problems. Regarding feeling guilty about sexual problems one-third (34%) of women had always felt guilty before implication of the program. Also less than one-third (32.9%) had felt both dissatisfied and angry about their sex life at pre-program. However, the same table indicates (post-program) that more than half (61.4%) and (57.1%) of women rarely felt guilty and regrets about sexual relationship, respectively. Regarding happiness about sexual relationship more than half (55.7%) of women had rarely felt unhappy, more than half (52.9%) had rarely felt inferior because of sexual problems, and more than half (51.4%) had never both felt frustrated and angry about sex life respectively at post intervention.

Sexuality is an important part of normal human functioning, but this is one aspect of care that has been largely ignored by health care providers for a number of reasons. While patients want to talk about this issue, they want the health care provider to raise the topic. In turn, health care providers are reluctant to initiate the discussion, preferring to wait for the patient to voice concerns. [53-58]

Egypt is a country where sexuality is not talking, about within the family; sexual education is not included in the curriculum of schools. Sexuality is regarded as shameful and guilty in this community that is becoming more and more conservative. In Egypt, since many parents received no education regarding sexuality from their parents, they do not have much knowledge about sexuality and generally avoid spoken about the theme with their children. Loss of sexual health education in the curriculum of schools giving health education causes problems regarding the assessment of a patient’s sexual health, the discussion of their sexual problems. [59]

There are some relatively simple strategies to include sexuality as part of clinical care. The first is to address personal attitudes that may be preventing the health care provider from including this topic in physician or nursing assessment and care. Personal attitudes to sexuality need to be assessed, and this can be done privately or at workshops, where opportunities for discussion abound. [60]

In the light of the previous, the researchers conducted this study for evaluating the impact of an educational nursing program of intervention on sexual dysfunction among women with cervical cancer. As regard to age as of the studied sample as a part of demographic characteristics of the study subjects, the present study indicated that slightly more than half of the study sample their age more than 50 years old. Similarly, to current study findings, (Zhou et al., 2017) that study "Patterns and predictors of healthcare-seeking for sexual problems among cervical cancer survivors: An exploratory study in China", found that slightly less than half of women their age ranged from (46-55) years old. [61]

Education has been showed to be a source of empowerment for females. Concerning to educational level of women, the results of the current study indicated that, slightly less than half of the studied women had secondary education and two-thirds were housewives. This also supported by Zhou et al., (2017) found that about half of the patients had education up to Junior high school level or less. [61]

Regarding to medical and surgical history of the study sample slightly less than three-quarters of patients had diagnosis of cervical cancer from signs and symptoms through health care provider while slightly more than one-third of women were in the 1st degree when diagnosed with cervical cancer and slightly less than one-third had second and third degree respectively.

In the same line with our study findings Soliman & Abd-Elsalam (2018) that conduct their study in Egypt to evaluate the Effect of "Standardized Oncology Nursing Care Intervention on Reducing Sexual Dysfunction among Cervical Cancer Survivors' Women" distributed the stages of cervical cancer among women, which IIB represented 16%, IIIA represented 30%, IIIB represented 32%, and IVA represented 22%. [62] Moreover, Ahmed & Hassan (2016) illustrated that slightly more than half of their sample detected cervical cancer by a doctor. [63]

Regarding type of treatment that received by the participants of the current study, the results showed that slightly more than one-third of women had received combined radiotherapy, chemotherapy, surgical operation. This finding is supported by Ahmed & Hassan (2016) illustrated that about slightly less than half and slightly more than one-third were in cancer stage II, III respectively. Regarding the type of treatment slightly more than one third of the studied sample was treated with surgery combined with chemotherapy and radiotherapy. The majority of the studied sample was having hysterectomy. [63] In disagreement, to current study findings, Zhou et al (2017) that conduct in China revealed that majority of patients in their study were suffering from stage II or lower stage cancer and having received combined treatment. [61] This may be related to as with increasing cervical cancer degree the need to use combination therapy increases.

Regarding to scores of female sexual functions index (FSFI) (desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, pain) the current study findings showed all women (100.0%) of the studied suffered from sexual functioning at pre-program, This may be this may be related to embarrassment, lack of access to information, low education about sex and ignorance of communication about sexual concerns by the health care provider. This percentage changed to 50% at post-program.

This is supported by Afiyanti et al., (2016) that studied "Evaluating sexual nursing care intervention for reducing sexual dysfunction in Indonesian cervical cancer survivors" stated that nursing care intervention on sexuality (FSFI) were statistically significant and alleviated dyspareunia (pain). Nursing care intervention also improved sexual satisfaction, which covered the second most improved domain. Vaginal lubrication and sexual desire of the respondents and their spouses were also improved. Orgasm was also improved. This may be due to high level of education among their studied women and their parteners. [64]

In agreement with our study result, Hassan et al., (2019) that studied "Comprehension of Dyspareunia and Related Anxiety among Northern Upper Egyptian women: Impact of Nursing Consultation Context Using PLISSIT Model" in Egypt revealed that there were statistically significant differences between pre and post application of PILLIST model (P<0.001) as regard to elements of female sexual function index (FSFI) including desire, arousal, orgasm, satisfaction and pain. [11] Moreover, Mohamed et al., (2018) that studied "Effectiveness of Application of PLISSIT Counseling Model on Sexuality Among Women with Dyspareunia" in Egypt revealed that there were statistically significant differences between pre and post application of PILLIST model (P<0.001) as regard to elements of female sexual function index (FSFI) including desire, arousal, orgasm, satisfaction and pain. [65]

Additionally, the result of the present study are supported by Mansour et al., (2014) that conduct a study about "The effect of sexual counseling program on pain level and sexual function among women with dyspareunia" In Egypt reported that statistical significant differences between pre and post FSFI scores in favor of post. All women's post-intervention mean scores were higher than pre-intervention mean scores. As showed that after counseling sessions; women's scores were higher than before with regard to desire, arousal, satisfaction, orgasm and pain. This may be due to continues motivation of women to address their sexual problems related to cervical cancer treatment. [66]

In congruent with the current study findings, Bakker (2016) that studied "A nurse-led sexual rehabilitation intervention after radiotherapy for gynecological cancer" During the intervention by using educational booklet about sexuality, Participants’ sexual functioning significantly changed over time compared to their situation before diagnosis. Participants reported lower levels of sexual functioning at 1 month. However, after treatment with rehabilitation therapy (RT), participants’ sexual functioning significantly increased over time. This may be due to after 1month of treatment sexual symptomes are vigrous related to treatment side effects and women fear to engage in any sexual activity. [67]

Regarding to women’s sexual distress scores; this study revealed that majority (88.6%) of the studied women had sexual distress at pre-program and all (100%) of them had no sexual distress at post-program. The results revealed regression of all items of women’s sexual distress scores post-program compared to pre-one.

In the same line with our study findings Ali, et al., (2018) that conduct a study about "Sexual distress and sexual function in a sample of Iranian women with gynecologic cancers" in Iran found that mean score for the FSFI was 19.4.This score reflects low levels of sexual function among the patients with gynecologic cancer. The mean total score for the sexual distress was 29.2 which also indicated low levels. [68]

In disagreement with the current study findings Bakker, (2016) stated that participants’ sexual distress was not significantly different over time. Compared to their pre-diagnosis situation, participants reported higher levels of sexual distress at 1 month and 6 months after treatment with RT and a trend for higher levels at 12 months after rehabilitation therapy. Also, after treatment with RT, participants’ levels of sexual distress did not significantly decrease over time during the intervention. This may be related to the study participants were evaluated early in the recovery phase, therefore, it should be noted that sexual distress among GCS may further recover between 12 and 24 months. [67]

The results of the current study revealed regression of all items of women’s sexual distress scores post-program compared to pre-one. Moreover, progression of all items of women’s sexual items post-program compared to pre-one. This may be attributed to the attending of the educational program sessions. [9,19,69, 70] In addition to supportive materials (educational booklet), also, played а crucial role in attaining and retain knowledge. The educational booklet which designed by the researchers based on review of literatures containing data regarding the following; (a) various sexual, and reproductive problems associated with cervical cancer. (b) Information and education on reproductive organs and sexual function, including anatomy and physiology of female genital system, explanation in the series of female sexual response cycle. (c) Types of sexual dysfunctions, dealing with sexuality problems, numerous relaxation and other exercises for improving sexual fitness (such as Kegel exercise, sensation focus exercise, and exercise of various technical positions during sexual intercourse). Booklets are best used when they are brief, written in plain language, full of good pictures and when they are used to back-up other forms of education. This is, in accordance, with Edgаr Dаle’s or the NTL’s Pyramid of Learning as cited by Mаsters as the pyramid illustrated that individuals can retain 10.0% of what they read and 20.0% of what they see and hear (audiovisual). The same author added that ones can retain 50.0% of what he learned by a discussion [71-80].

Based on the finding of the present study, it can be concluded that: The teaching program was very effective in improving sexuality and reliving sexual dysfunction & sexual distress for cervical cancer survivor women. So, the research hypothesis accepted.

Recommendations

In the light of the findings of the study, the following are suggested: